In December 2018, the United States Congress overwhelmingly adopted the First Step Act, which then-President Donald Trump signed into law. The law provided a way to allow inmates to earn credits toward reducing their sentence by up to a year by participating in programming and productive activities. In addition, credits could be earned to allow inmates to serve an unlimited amount of time on home confinement based on the number of credits they earned.

The First Step Act was not an easy ‘get-out-of-jail free.’ Instead, it was government realizing that something had to be done to reduce the number of people the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) houses in its 122 institutions across the country. The U.S. government estimates that it costs $120/day to house an inmate in an institution versus half that for allowing the inmate to be in community custody in a halfway house or home confinement. The First Step Act had two goals; 1) providing meaningful programming and activities in prison to reduce recidivism and 2) reduce the costs on incarceration.

Funding for First Step Act activities is significant. The Department of Justice’s FY 2024 Performance Budget to Congress includes base funding of $409.5 million for programs related to the implementation and continuation of the First Step Act. So there is a significant cost to the program that is supposed to lead to reduced costs of incarceration by transferring more prisoners to halfway houses or home confinement and by reducing the term through earned credits.

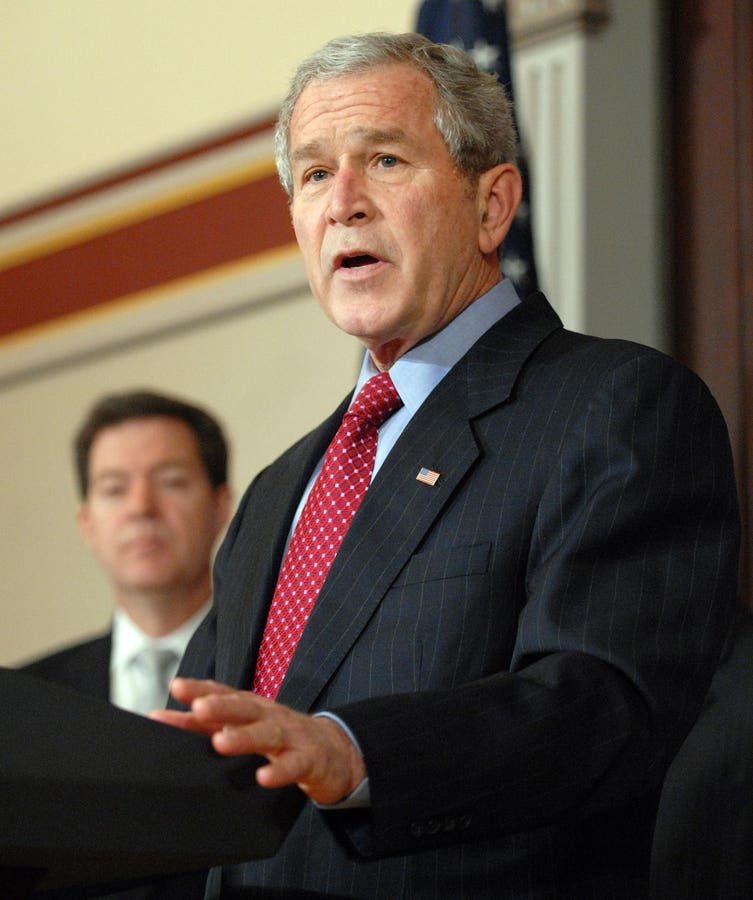

A similar humanitarian and cost savings approach was instituted with the Second Chance Act signed by George W. Bush in 2007. In President Bush’s comments on the signing he said, “The bill I’m signing today, the Second Chance Act of 2007, will build on work to help prisoners reclaim their lives. In other words, it basically says: We’re standing with you, not against you.” The BOP instituted this law which provided up to one year of halfway house placement, of which up to 6 months of that could be on home confinement. The program led to the expansion of halfway houses and most all prisoners leaving institutions, even those at the highest level of security, were able to spend a portion of their sentence integrating back into society. This transfer from prison institutions to community also represents a cost saving.

Each year, nearly 44,000 Federal inmates return to their communities, but could some of them have returned sooner? When the First Step Act was passed, it not only provided incentives to reduce the sentence, but it also reauthorized and expanded the Second Chance Act. So the intent was to place even more prisoners in alternative housing rather than prison institutions. However, in speaking with a number of prisoners who are nearing the end of their sentences, they say the Second Chance Act has all but disappeared.

I had written about one prisoner, Chris Mills, who could have been in the community for many months. Mills is now on home confinement but last November he was trying to get released from prison and into home confinement, something he had earned under the First Step Act. Mills earned 460 days of FSA toward prerelease custody (home confinement), meaning that he was supposed to leave prison for home confinement in October 2023. Under the Second Chance Act, he was also eligible for 180 days of home confinement …. he could have gone to home confinement on April 30, 2023. Mills finally left federal prison in January 2024 to home confinement because there was no room at the reentry centers. Had Mills been placed on home confinement, per what he earned under FSA and what he was eligible for under the Second Chance Act, he would have been home over 260 days sooner than what the BOP offered. At $60/day savings that is $15,600 for just one inmate.

This pattern is being repeated across the BOP where prisoners tell me the agency is not maximizing the use of policies and laws meant to get prisoners out of institutional living sooner. An example is a prisoner who has a 24 month sentence. They receive 108 days of Good Conduct Time off of their sentence and then another 180 days under the First Step Act. This means the prisoner will have fully completed their sentence after approximately 15 months. In addition, the prisoner can also be placed on home confinement for 73 days (10% of the sentence imposed). The prisoner can also be in a halfway house for another 10 months, but the BOP is not maximizing that. One reason is that halfway houses were meant to be used for transition for prisoners who have a real need for those facilities because of the need for housing and to reconnect. Many inmates, particularly those with shorter sentences (under 5 years) and who are minimum security, have housing so they really don’t need halfway house placement. Many of these prisoners would rather be out of the institution and closer to home but the BOP has nowhere to place them because of capacity issues at halfway houses.

The BOP provided a statement on the practice of using home confinement, “Home confinement is driven by two statutory authorities – the 2nd Chance Act and the First Step Act. Those eligible under the 2nd Chance Act may be placed in home confinement for the shorter of 10 percent of the term of imprisonment or six (6) months. They may not be in an RRC for more than 365 days. Those eligible under the FSA may be placed in prerelease custody (including home confinement) for the amount of federal time credits they have earned. The FSA removed the time limits for placement in prerelease custody. Home confinement is at the discretion of the FBOP and individuals must not only be statutorily eligible but must be appropriate and meet the requirements of the home confinement program.”

There are also problems with the BOP’s implementation of the First Step Act because it continues to struggle with the Projected Release Date (PRD). PRD is supposed to be used to predict when a prisoner is going to be released so that halfway house/home confinement can be determined. There is significant amount of work in processing a prisoner for release from an institution. One problem, particularly for those with sentences of 36 months or less, is the BOP is routinely using the current number of credits under First Step Act that have been earned and not considering the days to be earned in the future remaining portion of the sentence. This makes a huge difference because the paperwork to achieve the placement must be done months in advance. In some cases, prisoners are being given a date that they will be going to home confinement that will actually come after the prisoner is set to be released from custody. The result is that prisoners throughout the BOP are spending more time in prison than the BOP could return them to society.

There are three distinct groups of prisoners that are being held too long. The first are those whose sentences were just incorrectly calculated resulting in months of confinement that was unnecessary. While many of these errors occurred during the initial roll-out of the First Step Act, it took a lot of time to correct that. In one case written about here (US v Sreedhar Potarazu in the District of Maryland) had his First Step Act credits incorrectly calculated numerous times. In a court order recently released in his case, the judge wrote, “BOP admits that Petitioner’s earned time credits were incorrectly calculated several times. Specifically, BOP states that, in the first calculation of Petitioner’s ETCs on October 5, 2022, “two computer errors occurred which led to Petitioner receiving more credits and a greater time factor than he had earned.” On January 9, 2023, Petitioner’s ETCs were again miscalculated, this time giving him fewer credits than he had earned. Id. at 8. Finally, on January 19, 2023, BOP contends it correctly calculated Petitioner’s ETCs for a total of 570 FSA time credits: 365 toward release and 205 toward prerelease custody.” Still, there are miscalculations but they are far fewer.

The second group are those who have earned over 365 days of credit that reduced their sentence and then earn additional First Step Act credits toward home confinement. Many inmates report that due to limitations in halfway house capacity that they are not able to utilize those credits for home confinement and they stay in prison.

The last group are those inmates who can earn up to 365 days of halfway house under the Second Chance Act, and many inmates are not getting nearly that amount. Overall, this issue of housing inmates in prison longer than necessary, and for which the BOP currently has the power to transfer to the community, affects tens of thousands of prisoners, many are minimum or low-security inmates.

The BOP has the ability, but it is up to BOP Director Colette Peters to implement change that is within her power … something she has often spoken about.

Read the full article here