Seven decades after he became addicted to Superman, Gary Prebula’s collection of graphic novels and comics has a permanent home at the University of Pennsylvania library. It took a team effort.

By Kelly Phillips Erb, Forbes Staff

Gary Prebula blames his mother for his seven-decade-long comic book obsession. He was three when his parents ventured out on New Year’s Eve, leaving him with his grandfather. His mother bought a Superman comic book to keep the precocious toddler, who had just started to read, occupied. When his parents returned home just after 1:00 a.m. they found Prebula still awake, rereading that comic book, while his grandfather slept.

“I was addicted immediately,” he says. It became a constant of his childhood—each week, he’d walk three miles to the corner store in Butler, Pennsylvania, allowance in hand, to buy the latest superhero issues. In 1963, at age 12, he plopped down 12 cents to buy the first issue of The Amazing Spider-Man #1, the character’s solo-debut after Stan Lee introduced the teenage superhero in the Amazing Fantasy series the year before. Marvel’s The X-Men #1, another Lee creation, also cost him 12 cents that year.

Over the decades, the price of a comic book changed, but Prebula’s weekly ritual didn’t. He kept on buying comic books and later graphic novels, too, through adolescence, his graduation from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania in 1972, and his move to Los Angeles for grad school in film, and a career writing, directing and producing shows (including early reality TV shows), while teaching film courses at Cal State-Long Beach for 40 years. When Gary and his high school sweetheart, Dawn, married as teens in 1969, she knew he loved comic books. But it wasn’t until 1994, she says, when he had boxes of comics shipped from the old coal room of his mother’s Butler, Pa. basement to their LA home, that she fully appreciated the big and growing size of his collection.

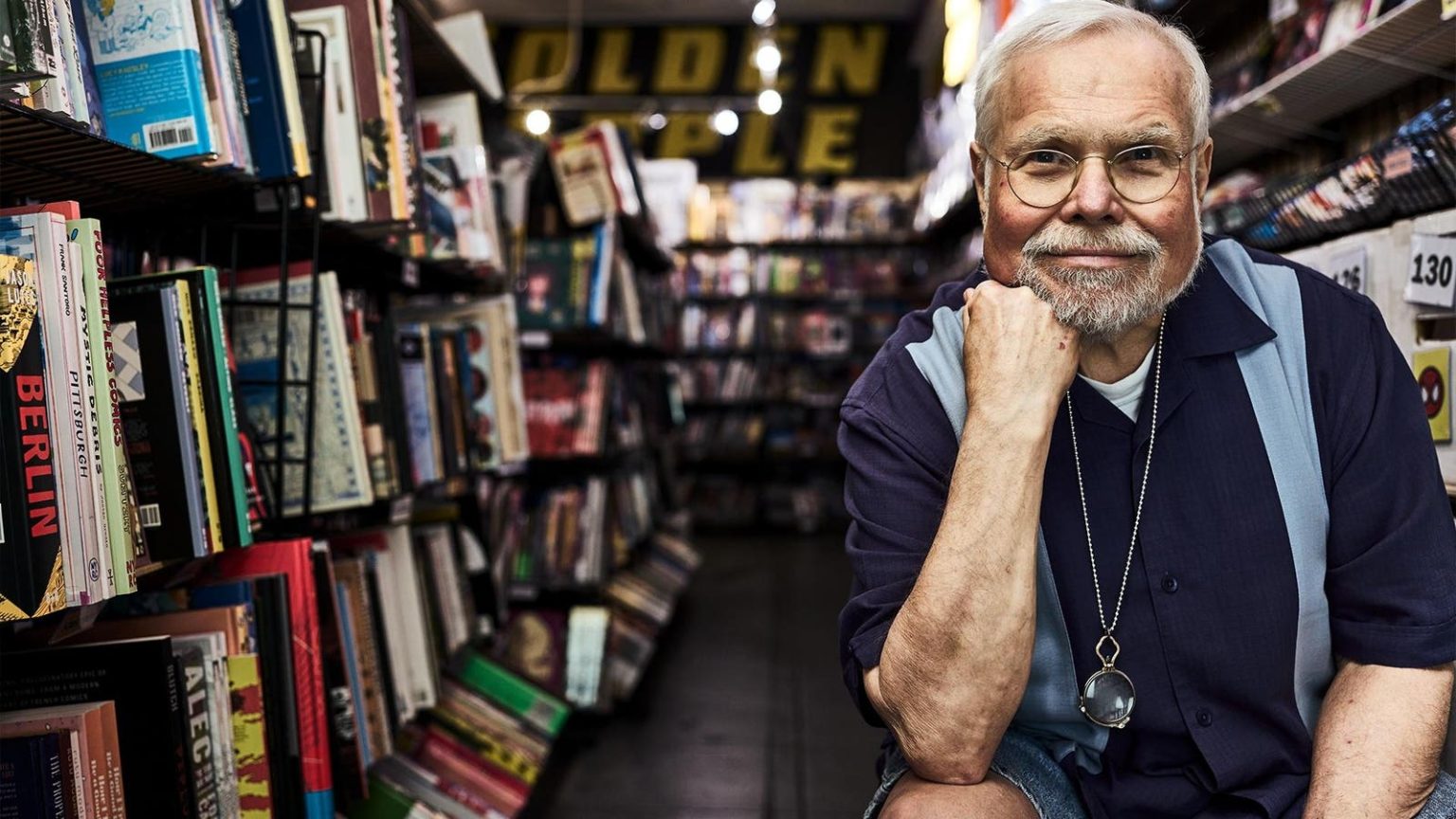

In the mid-1980s, Prebula found a new supplier to feed his habit: Golden Apple Comics. Bill Liebowitz, a CPA, real estate executive, and yo-yo champ opened the store as a 400-square foot hole-in-the-wall in 1979. By the time Pebula became a regular, Golden Apple was in larger quarters on Melrose Avenue and was earning a reputation as the “Comic Shop to the Stars,’’ with legends such as Lee, author Neil Gaiman and writer-illustrator Todd McFarlane, now the president of Image Comics, becoming regulars. About 50 to 100 new comic book titles would be delivered every Wednesday, and certain prized customers, including Prebula, would be given a sneak peek. Kids, he recalls, would pound on the windows, eager to get a look at the new arrivals as the adult VIPs strolled the stacks.

The idea that younger generations continued to seek out comics thrilled Prebula, but in his sixth decade of collecting, something began to gnaw at him. He had amassed nearly 80,000 comic books, and now wanted to make good on his lifelong ambition to share his collection and passion with future generations.

Fact is, despite his Wharton degree, Prebula had always been more an enthusiast than a profit-driven collector; he never sold his comic books for a profit and had even written his name in his prized Spider-Man #1–something a collector aiming to maximize an issue’s value wouldn’t do. Sure, he was a kid when he did it, but he had a reason. He hoped that in 100 years, someone would flip through it and wonder, “Who the hell is this guy?” he explains.

Prebula wasn’t the only one thinking about the future of his collection. Ryan and Kendra Leibowitz had been running Golden Apple since 2004, when Ryan’s dad died of a heart attack at just 63. So slowly, over the years, the couple started talking to their aging “Wednesday warrior” regular about what he planned to do with all those comic books.

The Leibowitzes could have made some money selling Prebula’s collection. But they were thrilled he planned to donate it to the University of Pennsylvania’s library because the school, as he put it, “gave me my life.’’ Kendra had worked with nonprofits, including the New York City AIDS walk, in her life B.C.—before comics—and saw an opportunity to get into the giving game again. Dawn Prebula, who confides she once believed Gary’s “collection could be sold eventually to help us when we got older” was also on board with the donation.

It turns out that donating comic books—let alone 80,000 of them— isn’t as easy as writing a check to your favorite charity, particularly if you want to maximize your tax benefits and assure your collection is available for study.

And Prebula’s comics weren’t precisely donation ready. Many fans of comic books will take significant measures to keep their collections in top condition, including storing comic books untouched (in their original clear bags) in climate-controlled rooms with low lighting. The value of comics goes up if they’re in pristine condition–they’re typically assigned a number of 1 to 10, indicating how “new” they might look and how well they have been preserved. For example, one copy of X-Men #1 with the first ever appearances of Magneto and Professor X in Prebula’s collection is graded at 6.0 and worth $22,000, while another copy he had is graded at a 4.0 and worth only $13,000. (By contrast, a mint condition X-Men #1 graded as a 9.6 sold for $800,000 in June of 2022.)

Though not in mint condition, many of Prebula’s comics were well-preserved (after retrieving the books from his mother’s coal basement, he built a special room under his patio that was cool, with a dehumidifier). But he hadn’t organized his holdings methodically, say, by genre or series, the way someone worried about future scholars—or donations to a library—might. Instead, he’d put them into boxes after he read them. That meant the hoard would require significant time to sort and catalog. Not all universities or museums have the resources to undertake that sort of project, making it more likely that they will decline the collection—or worse, take it and relegate it to storage for years.

A library accepting the collection was key, not only because Prebula wanted the issues to be read and studied, but also because of the tax rules when it comes to donating art and collectibles. The donor’s charitable deduction on his 1040 is limited to the cost of the collectible-i.e. 12 cents for The Amazing Spider-Man 1 or The X-Men #1—unless the item is given to a not-for-profit that can use the gift to further its charitable purpose. In that case, the deduction is equal to the market value of the collectible. Plus, each item valued over $5,000 must have a written appraisal by a certified appraiser (qualifications matter here, and the valuation methodology should be well-documented). Additionally, donors must file Form 8283, Noncash Charitable Contributions, with their tax return to claim a deduction.

All this made giving away Prebula’s collection a major undertaking. And to complicate matters, his eyesight was failing.

The collection was shipped to Ryan and Kendra Leibowitz’s house–it took two cargo vans full to the brim to make that move. Then, they began the hard work of organizing and cataloging the comics. At first, Ryan went through each box and found the issues that he believed had the most cultural or historical significance or were worth the most. They shipped those 561 single comics in six small boxes to Philadelphia in early 2023. Then, they focused on magazines, oversized comic books and the next tier of valuable issues. That was a bigger undertaking, so they used a combination of volunteers and paid help to separate the comics into batches. They sent a second and third shipment to Philadelphia, adding up to four pallets of boxes, later last year.

Meanwhile, the Leibowitzes had set up the Golden Apple Comic & Art Foundation, which received IRS certification as a tax exempt foundation in November 2021. Its mission: “to preserve, safeguard and showcase private collections to ensure that comics, books, art, and collectibles are secured for future generations to enjoy.” (It paid some of the sorting costs for the Prebula collection.)

It’s a tiny charity, but has a support list that reads like a Who’s Who of the comic world, including actor Keanu Reeves, who signed 50 prints from his own comic book series, BRZRKR–that raised $10,000 for the foundation. Kevin Eastman, who created the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and Tom Waltz signed a Last Ronin print (a TMNT comic book miniseries), which raised $4,000. And Frank Miller, known for his comic book stories in the Daredevil series (he created the character Elektra), screened his documentary, FRANK MILLER: AMERICAN GENIUS, turning over a majority of ticket sales.

The foundation isn’t just a Leibowitz family production. Kevin Smith, best known for such comedy films as Clerks, Mallrats, and Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back, is an associate board member. (Smith is a bona fide comic book fan and owns a comic book store in Red Bank, New Jersey.)

Kendra Leibowitz says the Golden Apple foundation aims to act as a middle man, finding library homes for additional private collections and getting them ready for donation. In one instance, she says, there is a tremendous pulp collection (those are cheap fiction mags printed until the mid-1950s and named after the material they were printed on) that she’s trying to place. That has resulted in a lot of hours on the phone. It’s still early, she says, but she’s hoping Bowling Green University—with its well-known academic department and library specializing in American popular culture—might be interested. She hopes to eventually build a database of what universities and museums want and don’t want and to open a little museum—maybe a mobile one—to make comic book art and history accessible to fans and future fans. “So many amazing creators are gone,’’ Ryan says, “and we want the next generation to know what we did.”

The Prebula donation is a big deal for the Penn library, too. Sean Quimby, director of the library’s Jay I. Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, says pre-Prebula, the collection held just 20,000 comic books and 4,000 related materials, including graphic novels and compilations.

The collection is now going through more processing, by both librarians and by an appraiser hired by the Prebulas. (While the collection is worth north of $500,000, it’s up to the appraiser to determine its final value for tax deduction purposes.)

Quimby expects the collection to become available “in some form” by next year. He doesn’t mind that it isn’t in perfect condition—comics are often printed on highly acidic paper, making them vulnerable to damage. But they’re in good enough condition to be used for research, teaching and public exhibitions. “While we house extremely valuable and rare things, we are not just a repository for expensive stuff,” Quimby says. “We are not just an attic.”

That’s good news for Prebula, who wants his collection to be seen and used. It was, he said, “very painful…to give the comics away.” He admits that he couldn’t sleep the night before all his boxes were moved to the Leibowitzes. He was tempted to keep The Amazing Spider-Man #1–the one he had signed– but he didn’t.

Anyway, Dawn, now 73, and Gary, now 74, have a new retirement project: golf. But they’re not just swinging clubs–in December 2019, they, along with their son and daughter-in-law, bought the Slippery Rock Golf Club and Events Center in Pennsylvania, with 183 acres, 18 holes, a full-service restaurant (The Twisted Oak Tavern) and spaces for weddings and events. Today, Dawn manages the club–which will turn 100 in a few years–with help from the Prebulas’ son, daughter-in-law and granddaughter. (Their grandson also works there.) They also own a B&B–the Applebutter Inn–two miles away.

Gary, for his part, keeps busy staying true to his roots. He’s finishing the third book in a young adult book series with plans to write more and sell the series to a publisher. “For someone who has been reading and collecting comics books for nearly 70 years, he should know something about what young adults want to read,’’ says Dawn.

As for the comics at Penn, Gary says, “Someday, I’ll go visit them.”

MORE FROM FORBES

Read the full article here