Tax Notes senior legal reporter Nathan Richman discusses the tax implications of the recent financial controversies surrounding Los Angeles Dodgers player Shohei Ohtani and his former translator.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

David D. Stewart: Welcome to the podcast. I’m David Stewart, editor in chief of Tax Notes Today International. This week: curveball.

There’s always a tax angle, and this week, we’re finding it in America’s favorite pastime.

Shohei Ohtani is possibly the biggest star in Major League Baseball today. He’s a unique talent and the recipient of the largest free agent contract in baseball history. Recently, his name has crossed over from the sports pages to the tax press, for both the structure of his contract and a tax fraud scandal swirling in his orbit.

Here to talk more about this is Tax Notes senior legal reporter Nathan Richman. Nate, welcome back to the podcast.

Nathan J. Richman: Thanks for having me.

David D. Stewart: All right. So, start us off with an explanation of who is Shohei Ohtani?

Nathan J. Richman: As you said, he’s one of the, if not the biggest baseball player at the moment. He’s the first player in a very, very, very long time who is both a star pitcher and potential batting champion. So, in this past off-season, he got a $700 million 10-year deal to go from the Angels to the Dodgers. A startling commute across the vast city of Los Angeles.

David D. Stewart: Now, this is his second commute. So, where did he start off playing?

Nathan J. Richman: Well, he comes from Japan, and that’s where he started his career. And his lack of English to date is part of the trouble that has led us to start discussing him.

David D. Stewart: So, before we get into the most recent troubles, tell me about this massive contract.

Nathan J. Richman: As I said, it’s $700 million over 10 years, but the structure of the deal has been riling particularly the state of California, because it’s structured to be $2 million a year for those 10 years of play with the bulk coming afterwards. And the California tax authorities are a little concerned that they might not get to tax most of that money.

David D. Stewart: So, what is the problem? Why can’t they get ahold of their due from this giant contract?

Nathan J. Richman: Well, let’s just assume he moves back to Japan afterwards. California no longer has jurisdiction over him. We’ll see if the U.S. tax authorities still think they have jurisdiction over him if that happens.

David D. Stewart: So, has anybody taken actions since this contract was put in place?

Nathan J. Richman: Well, according to my colleague Paul Jones, some California officials have written to Congress to try to put some sort of limit on these sorts of deferrals.

David D. Stewart: All right. So, let’s get into this recent issue. I understand it involves Ohtani’s translator and some money that went missing?

Nathan J. Richman: Ippei Mizuhara, the man Shohei Ohtani brought over from Japan to be his translator, hired by the two teams at various points and also working separately for Ohtani directly, apparently stole nearly $17 million during that time to fund a pretty substantial gambling habit.

David D. Stewart: OK. So, we have this substantial theft. How does the IRS get involved?

Nathan J. Richman: Apparently, through some joint investigation between the IRS’s Criminal Investigation division and Homeland Security investigations into some illegal bookmaking in Southern California. This led first to a criminal complaint filed against Mizuhara, filled with all sorts of salacious and interesting details about his conduct from approximately 2021 to early 2024. And then more recently, to a negotiated plea agreement between Mizuhara and the government.

David D. Stewart: So, what sort of things was he getting up to?

Nathan J. Richman: Well, apparently, Mizuhara got hooked on online gambling through this not exactly aboveboard gambling site. The complaint describes his total activity over those few years as approximately 19,000 bets placed at a rate of maybe 25 a day. Mizuhara won $142 million from those bets, but he lost $183 million. Of course, this means lots of interesting text exchanges described where Mizuhara is talking with the bookies: How does he pay; what’s his limit? Things like that. But eventually, degenerating into a discussion of the bookies being very perturbed that some of their money, this $40 million of net losses, wasn’t being paid.

At one point, one of them sends him a rather ominous text saying that the bookie is watching Ohtani walk his dog, and suggesting maybe going up and talking to Ohtani about the subject would get Mizuhara to return his calls. There was one potentially useful clarification for Ohtani at the very end of this complaint. When the allegations first started coming out, there was speculation that Mizuhara wasn’t really betting on his own but was just placing his boss’s bets. The very last text exchange described has the bookie saying, “This is all bull, right?” in a question to Mizuhara, who then responds, “No, no, I technically stole from him. I’m up a creek.”

David D. Stewart: All right. So, we’ve got a lot of criminality going on here. Where is the tax angle to this story?

Nathan J. Richman: So, I read these reports and I started thinking to myself, can Ohtani deduct these theft losses? What happens to Mizuhara? Is he going to have to report $140 million of income from his gambling wins? Will he get charged with a tax crime? And what about just the $16 [million] or $17 million he stole?

Starting with the theft loss. Generally, when you’ve discovered a theft or other sorts of casualty loss, there can be a deduction under section 165. Theft loss often involves two main issues. Can you prove that your loss was actually a theft? And also, when can you take it? The first, Mizuhara’s text and the related criminal proceedings probably will help Ohtani with, but the timing in theft loss deduction cases can get very interesting. The losses are deductible when they’re not otherwise compensable. So, you have to prove that there’s no chance you’re going to get the money. In theft loss, it’s usually discussed in terms of a reasonable prospect of recovery. Will insurance pay for it, or do you have somebody else you can go after? The criminal case against Mizuhara complicates things even further, because there’s a possibility of restitution or some sort of forfeiture paid to the government, that could then be used to pay Ohtani.

Another curveball on timing comes from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which has a broad limitation on personal casualty loss deductions, at least up through the end of 2025, which could mean Ohtani would prefer to not have exhausted his reasonable prospects of recovery for a year or so. Switching sports, of course, the Super Bowl of taxes — the negotiations over the TCJA extensions coming in 2025 — could throw that plan out of whack.

David D. Stewart: All right. Now, I am only passingly familiar with the concept of how you treat gambling wins and losses. This is another area that seems ripe for exploration, which you mentioned earlier. So, what’s going to be happening there?

Nathan J. Richman: So, the basic concept for gambling, especially for ordinary gamblers, is this concept of basketing, which is to say gambling losses are deductible only to the extent of gambling gains, which is to say, you put all your gambling activity in this little basket. If there’s a net income, you have to report it. If your losses exceed your income, you come out with a zero effect on your end tax structure. This gets complicated, especially for amateur gamblers, because the way the basketing works is through miscellaneous itemized deductions, which is to say, you don’t get your standard deduction if you need to offset, say, nine figures of gambling losses.

David D. Stewart: What does that mean for Mizuhara?

Nathan J. Richman: It means that probably over the course of those years, he will be able to fully offset. Now, professional gamblers used to have a better tax result, because they could deduct losses exceeding their wins and also could throw in all sorts of other gambling-related expenses, travel, rooms, etc. But the TCJA rears its head here as well in forcing professional gamblers to have a pretty similar treatment to amateur gamblers. So, despite his voluminous time-intense activity, it might not be worth it for Mizuhara to try to claim to be a professional gambler.

One other thing that would go into the professional question would be any use of his expertise. And everybody’s been very careful to point out that none of his betting activity involved baseball, and there’s no reason to think that he knows much about other sports.

David D. Stewart: All right. So, I guess, the other pot of money that we have to talk about here is the money that he took. Is there going to be a tax liability on that?

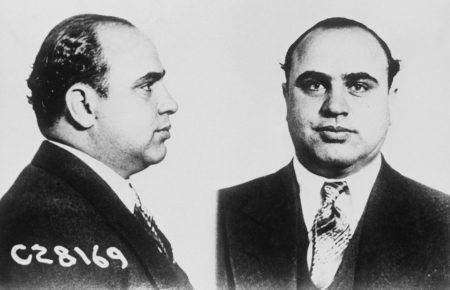

Nathan J. Richman: Well, it’s been well established for a very long time that illegal income is still reportable income. Just ask Al Capone.

David D. Stewart: So, are we in a situation where he could potentially have to report the $16 million of theft and then offset it with his gambling losses?

Nathan J. Richman: So, because of that gambling loss basketing, he probably won’t be able to use that $40 million of net gambling losses to offset the $16 [million] to $17 million of net theft income that he has.

David D. Stewart: So, tell me about pending criminal charges going on here.

Nathan J. Richman: Mizuhara recently entered into a plea agreement to plead guilty to one count of bank fraud, because he stole all of this money by using Ohtani’s login information to manipulate the bank account that Ohtani had his Angels’ salary deposited into, to take that money and pay off the illegal bookies. And also because of all that undeclared illegal income, he’s facing a false return charge.

David D. Stewart: All right. I guess we’ll have to see how this all plays out. Nate, thanks for being here and explaining it all to us.

Nathan J. Richman: Thanks for having me.

Read the full article here